Iceland – land of fire and ice

Iceland – the famed land of fire and ice. Any earth scientist dreams about traveling to the mythical island nestled in the north Atlantic. However, its prestige extends to an exceptional degree in the world of geology. Iceland is the product of hot spots (a hole in the earth’s crust that creates a volcano) and divergent margins (the volcanic rifts that create the world’s ocean basins) existing in the same place. The rocks and topography of the island demonstrate some of the most riveting and monumental geologic processes in the world.

Iceland – the famed land of fire and ice. Any earth scientist dreams about traveling to the mythical island nestled in the north Atlantic. However, its prestige extends to an exceptional degree in the world of geology. Iceland is the product of hot spots (a hole in the earth’s crust that creates a volcano) and divergent margins (the volcanic rifts that create the world’s ocean basins) existing in the same place. The rocks and topography of the island demonstrate some of the most riveting and monumental geologic processes in the world.

This July, I had the privilege of traveling to Iceland with CRMS geology teacher Kayo Ogilby, Ellie Urfrig ‘22, Bryn Peterson ‘21, and Tristan Trantow ‘23 to “Bikepack Divergent Margins”. It was an undoubtedly harsh, yet glorious introduction to the world of bikepacking (a marriage between backpacking and off-road cycling).

The impetus of our trip was to film the second episode of the Earth Science Adventure Diaries – a YouTube series that seeks to tell earth science and geologic stories through the lens of adventure. For the first episode, Kayo traveled with CRMS alumnus Bryn Peterson to Castle Valley, Utah, for his senior project. They told the story of evaporite deposits left by an ancient seaway by climbing a spire in the area.

Our first day of biking was marked by an all-day, non-stop torrential downpour that soaked us to our bones. However, we gazed through the clouds at sharp cliff walls that rose out of the flat ground and into the abyss, and as we approached those cliffs, our bike computers would alert us that we were “Entering Hayaloclastite” (a rock formed from the subglacial eruption of a volcano). We were immediately and intimately invested in any change in the geologic setting.

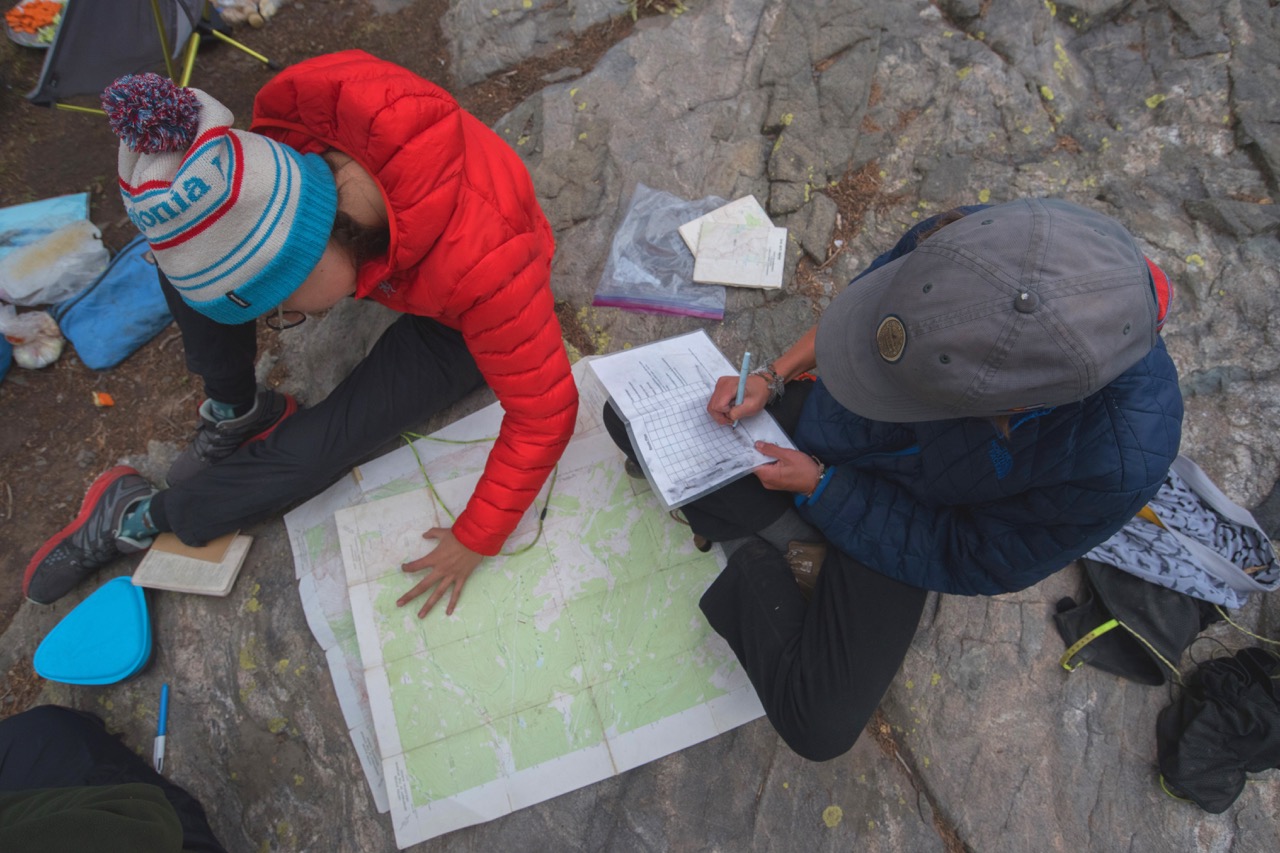

My senior project was to program our bike computers to do this, build our bikepacking route, and conduct a geological analysis of the route using GIS (Geographic Information Systems) software. As a result, the geology became as much of a character in our trip as the weather, our bikes, or each other.

The second day of the trip brought us another classic feature of cycling in Iceland: endless stream crossings. At the first one, we were faced with the never-ending question of whether to walk or ride through the deep water. I went for it – fresh snowmelt came splashing up just below my axels, but I made it through with only wet feet. “It’s not so bad,” I thought, “I’ve got my neoprene booties.” Little did I know that was the first of twenty-plus frigid crossings ahead of us. As we climbed further into the highlands, the temperature dropped into the low forties with a cooling breeze at our backs, but the desolate, moonlike landscape distracted us from the fact that our toes were slowly numbing. The more streams we crossed, the more apparent it became that we had to keep moving in order to stay warm. Stopping too long to eat meant dangerously cold toes, so we rode mostly in silence, intermittently shoving pocket snacks into our mouths to prevent a total bonk. Luckily, we quickly reached the hot springs at camp, and our toes were warmed.

Over the next week, we persevered the stream crossings and near constant threat of rain as we traveled north then west back towards Reykjavik. As our trip came to a close, we approached a location that would encapsulate our episode title of “Bikepacking Divergent Margins.” The whole day, our hearts raced in nervous, giddy anticipation; we bounced back and forth on ideas of how best to capture the crucial crossing. We all giggled at each other as we crested our last hill before the ever-awaited descent into Thingvellir. Then, there it was: a giant crack in the earth, signifying Iceland’s location over the volcanic rift valley that created the Atlantic ocean. A classic Icelandic rainbow appeared in the distance, but we had no desire to find its end. We had just struck gold – we bikepacked across a divergent margin.

During the final miles of our ride back to Reykjavik, I reflected on the creation of the trip and how it spanned the two worlds that CRMS so beautifully embodies – outdoor adventure and academic inquiry. CRMS granted me the skills and curiosity to explore my boundaries in the outdoors and to bring that growth back into the classroom. Moreover, the school taught me that what you learn in the classroom often seamlessly extends into the environments we hold dear. That narrative is the goal of the Earth Science Adventure Diaries. The only question remaining is what landscape and adventure is next?

MYCRMS

MYCRMS

Virtual Tour

Virtual Tour