Emily Bray ’75 Pioneers Dinosaur Egg Research

Emily Bray never imagined she’d be at the forefront of dinosaur egg research when she was growing up. Her journey from nature enthusiast to pioneering paleontologist is a testament to the power of curiosity and the right educational environment.

During high school, when her family moved to Libya, there were no English language schools. As a result, Emily found herself at Colorado Rocky Mountain School, which became “the perfect fit” for her education. At CRMS, faculty members like botany teacher Dick Herb and ornithology teacher Jerry Wooding nurtured Emily’s love for the natural world.

After a brief stint in college and some soul-searching, Emily landed a job at Canyonlands National Park, thanks to Gene Hebert. This experience ignited her passion for geology. She returned to her studies at the University of Colorado, where paleontologist Martin Lockley introduced her to dinosaur tracking.

“Tracking made sense because growing up I followed game trails, looking for scat and tracks,” Emily explains. “Looking at dinosaur tracks from millions of years ago was just so interesting to me.”

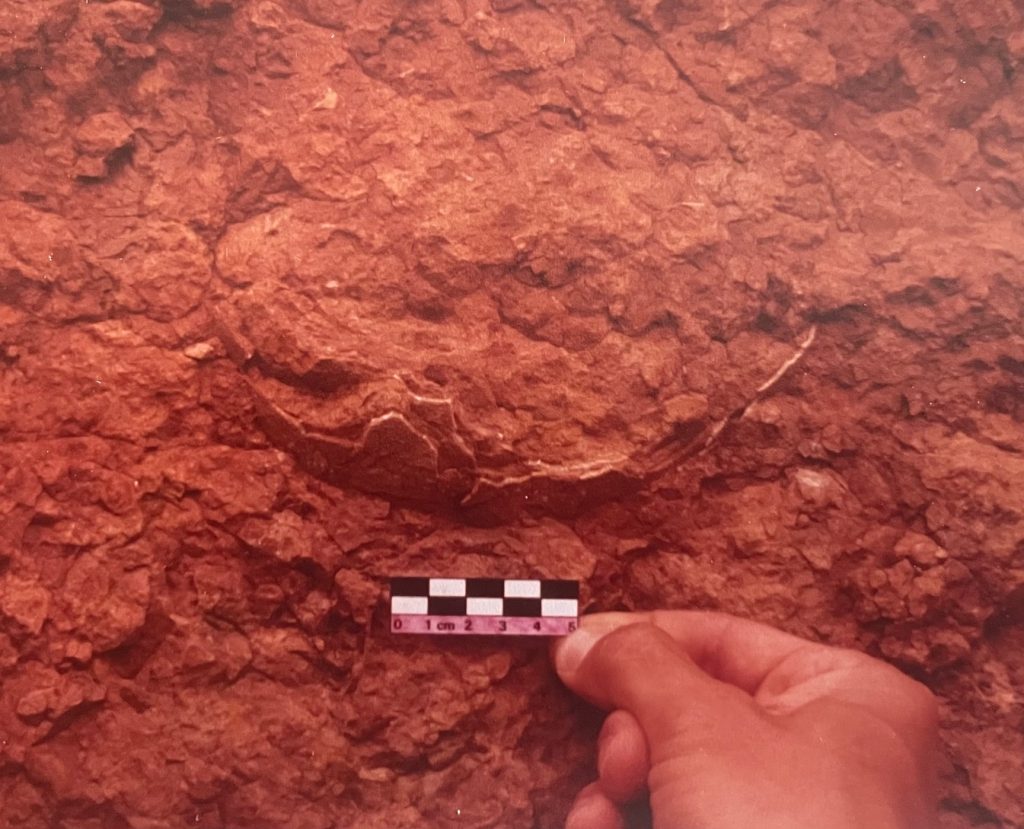

Some of the tracks would be exposed on the surface, while others required some excavation. Emily realized that her days at CRMS helped her to see tracks in a distinct way. “I got an eye for it and learned to see them,” she shares. “My immersion in the natural world at CRMS helped nurture that ability to see things others may not.”

She explains, “CRMS stimulated me on the academic side, especially the sciences, and exposed me to long periods out in nature on Wilderness, Fall Trip and Spring Trip. CRMS fostered a deep abiding love for the outdoors and helped me hone my perception of the natural world.”

Emily remembers being on her solo during Wilderness and thought it was such a gorgeous time to sit and listen and perceive. “I had all of my senses open without any agenda. To just be and be present and take in everything around me helped me to see things with some clarity.”

One set of tracks was ceratopsian tracks outside of Golden in a clay pit. While on private property, they had been exposed and people had walked by them for years but no one saw them for what they were until Emily’s team came along. Similarly “the Alameda tracks across from Red Rocks had been exposed and known since the 1930s. No one had really analyzed and studied them though.”

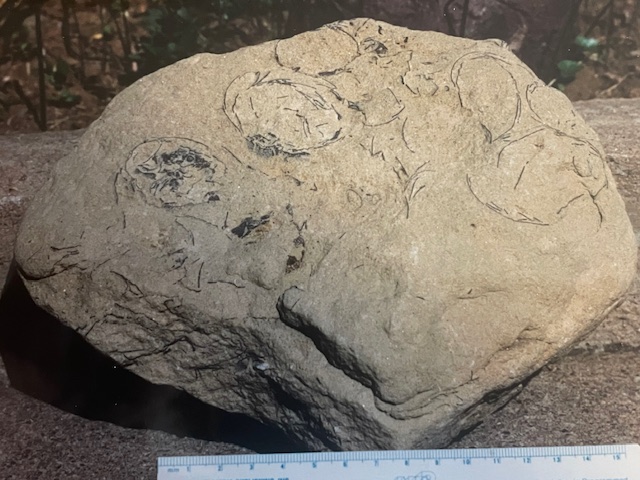

In the 1980s, Emily found herself at the forefront of dinosaur egg research. Fossilized dinosaur eggs had been found in Mongolia as early as the 1920s but no one really knew which animal had laid them. Not until 60 years later, did Emily and her colleagues around the world start to study these eggs to understand their structure, chemistry, and origin species.

Working with a small international team, she studied microstructures of modern animal eggs to extrapolate information about fossilized dinosaur eggs. A breakthrough came in the early 1990s when a fossilized dinosaur embryo was discovered, allowing researchers to definitively link an egg to a specific species.

Emily’s career as a paleontologist has been supported by the University of Colorado Museum, grants, and self-funding which has allowed her to travel the world going on expeditions with fellow scientists that included paleontologists, paleobotanists, ornithologists, and geologists. She loves the collaborative nature of dinosaur egg research and getting to work with an international group of men and women who have broadened her perspective overall.

What has been the best part of her work? “The joy of discovery. There’s always something new and exciting. I love having my mind blown by unexpected new things and the surprise of not knowing where something will take you.” Emily loves looking at the past and asking questions. “Science goes down the path of whoever’s asking the questions.”

And Emily got to ask some pioneering questions about dinosaur eggs and help the world better understand these incredible creatures.

MYCRMS

MYCRMS

Virtual Tour

Virtual Tour