New Course Spotlight: Videography and Animation

The south end of campus, bordered by a cow pasture, braided by irrigation ditches, and buttressed by the majestic double-peak of Mt. Sopris, serves to house the multifaceted art department of the Colorado Rocky Mountain School. Like the classes, the buildings themselves reveal the eclecticism of their disciplines. The octagonal jewelry hogan houses the saws and soldering irons of the silversmithing program. The beehive-shaped, student-stuccoed “Adobe” hosts the drawing and painting classes. The forge, furnace, and kilns of blacksmithing, glassblowing, and ceramics are clustered within the Whitaker Building. And the sounds of strings and percussion instruments boom from within the Weber Music building. The photography classes have found their home within CRMS’s most iconic building, known simply and fondly as “the Barn.” And the latest addition to the CRMS art course list, Videography and Animation, can be found in the classrooms at the back of the Barn, where students gather to make cinematic magic with visual storytelling.

The south end of campus, bordered by a cow pasture, braided by irrigation ditches, and buttressed by the majestic double-peak of Mt. Sopris, serves to house the multifaceted art department of the Colorado Rocky Mountain School. Like the classes, the buildings themselves reveal the eclecticism of their disciplines. The octagonal jewelry hogan houses the saws and soldering irons of the silversmithing program. The beehive-shaped, student-stuccoed “Adobe” hosts the drawing and painting classes. The forge, furnace, and kilns of blacksmithing, glassblowing, and ceramics are clustered within the Whitaker Building. And the sounds of strings and percussion instruments boom from within the Weber Music building. The photography classes have found their home within CRMS’s most iconic building, known simply and fondly as “the Barn.” And the latest addition to the CRMS art course list, Videography and Animation, can be found in the classrooms at the back of the Barn, where students gather to make cinematic magic with visual storytelling.

The Videography and Animation course description makes an ambitious claim: “this course is for any student seeking complete creative freedom.” Calvin Bates, the teacher making this bold claim, explains, “I view making a movie as having complete creative control over what your audience is experiencing. You choose the visuals, sound, and what the actors say.” According to Calvin, when it comes to animation, in particular, “the only limitation is your imagination. There’s really no limit to what you can express.”

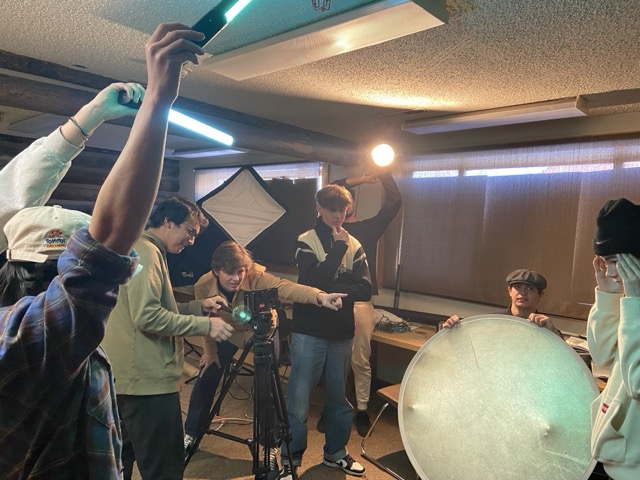

Calvin’s goal with Videography and Animation is to give his students the skills and tools to effectively express what they are hoping to. With the right mix of visual and auditory tactics, Calvin believes that his students, like the directors and cinematographers they study, can tell a story and make their audience feel joy, anger, sadness, or any number of emotions. In fact, for an upcoming project, students will do just this. Calvin will ask his students to produce a 30-second video that evokes a particular mood using light arrangements and deliberate color palettes. The students are primed for this project, having just recently completed an assignment to recreate famous portraits. They were tasked with replicating the lighting within the original painting with artificial lights and lightsticks in their photographic reproduction. Sophomore Frances Jansen, for example, recreated Jamie Wyeth’s iconic portrait of John F. Kennedy.

The class is divided into skill units, and each new skill typically receives two weeks of class attention. Calvin uses the first class of the unit to introduce new concepts and techniques. He taught a lesson earlier in the fall, for example, on “frame composition,” emphasizing the classic “rule of thirds,” in which a frame or canvas is divided into thirds vertically and horizontally; objects are placed in either the leftmost or rightmost third to produce a compelling composition. He also introduced cinematographic techniques for deliberately guiding the viewers’ eyes within the frame by creating angles that lead the eye directly to the subject or even creating a frame within a frame. Senior Makai Yllanes notes that Wes Anderson’s aesthetic, as exemplified in The Royal Tenenbaums, has been a source of many class exemplars as well as a personal influence on his own work. Makai explains that in addition to Wes Anderson’s composition (and his classic symmetrical shot), the color and costuming of Anderson’s scenes create a cohesive visual style.

After providing instruction on new concepts and skills, Calvin shows his class examples from television shows and movies, like those of Wes Anderson or cinematographer Roger Deakins (known for his work with color and light). Calvin provides enough models to guide the students but not too many to trammel the generation of original ideas.

However, the vast majority of time within a skill unit is dedicated to student experimentation and production. Calvin assigns a project that emphasizes the new technique and his students will plan, film, and edit a video to be shared with the class at the end of the unit.

For each new project, Calvin stresses the importance of the planning process, asking students to submit scripts and make revisions before even thinking about the camera. Once the narrative ideas are in place, students storyboard their film (a process of physically sketching out each shot so that the visual elements are accounted for in every frame). After designing the lighting, selecting the lenses, choosing the camera angles, planning the duration and distance of each shot, coaching the actors, and developing the auditory elements, the students are finally ready to begin shooting their films. “I want the students to get into the weeds,” Calvin says, “before they start filming.”

Even though a great deal of planning takes place before each project, the prompts themselves are open-ended. They include specific technical requirements, but the students have the freedom to take the projects where they want to go, and with some frequency, this means that humor is a quintessential element of student work. Charged with filming two-minute training montage sequences, students’ ideas veered directly toward comedy: one group filmed a training sequence for rock-paper-scissors competitors, another group found humor in a montage of mopping, and another depicted the training regimen of Batman’s protegé. The students consistently create visual vignettes suffused with personality and personal style. The films begin to have their individual fingerprints, voice and vibe, much like the professionals they emulate.

“Given the digital age we live in,” Calvin explains, “I want this class to peel back the curtain on videography techniques. I want the students to view the media that they’re consuming through a lens that makes sense, [for the students to understand how the] visual tactics are being used to make people feel a certain way.”

Not only are Calvin’s students able to identify the techniques of composition and lighting that influence a viewer’s emotional response, but the students are also increasingly able to craft their own narratives and control the emotional impact of their work. They are beginning to understand how technical skills and conceptual guidelines unlock the door to total creative freedom.

MYCRMS

MYCRMS

Virtual Tour

Virtual Tour