The Intersection of Math, Geography and the Built World

Eric Brown De Colstoun ’82 leads satellite-based research on urbanization, and land cover and land use change for NASA

Eric Brown De Colstoun ’82 leads satellite-based research on urbanization, and land cover and land use change for NASA

“You do know we have a rover on Mars named Curiosity?!”

Curiosity has defined quite a bit of Eric Brown De Colstoun’s childhood, education, and professional life. Quick to point out that he was not involved in the wildly successful Mars rover mission that shares the name of this CRMS value, his research and professional work at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, MD, reflect the joy and impact that an inquisitive mind can have.

Born in Brazil to a father from France and a mother from North Dakota, Eric’s early life involved important, formative experiences with the natural world. In his early school experiences, he attended a French-language primary school (Colegio Francia) while his family lived in Caracas, Venezuela.

“Venezuela is a beautiful country, full of beautiful landscapes and biomes, from pristine tropical forests to savannas, and thousands of migratory birds and other life. Living there inspired in me a real appreciation for the natural world. It’s part of what got me interested in natural resource management.”

As a child, his interest in Venezuelan baseball sparked a corresponding interest in mathematics. “The reason I became a math major is that I used to track statistics as a kid for the Venezuelan baseball players in the Major Leagues. And I just loved numbers.”

A family place in Vail and improving his English-speaking skills brought Eric to CRMS in the fall of 1980. Like so many alumni who initially choose CRMS for one thing, becoming immersed in the unique environment of the campus and the Roaring Fork Valley had a powerful effect on him.

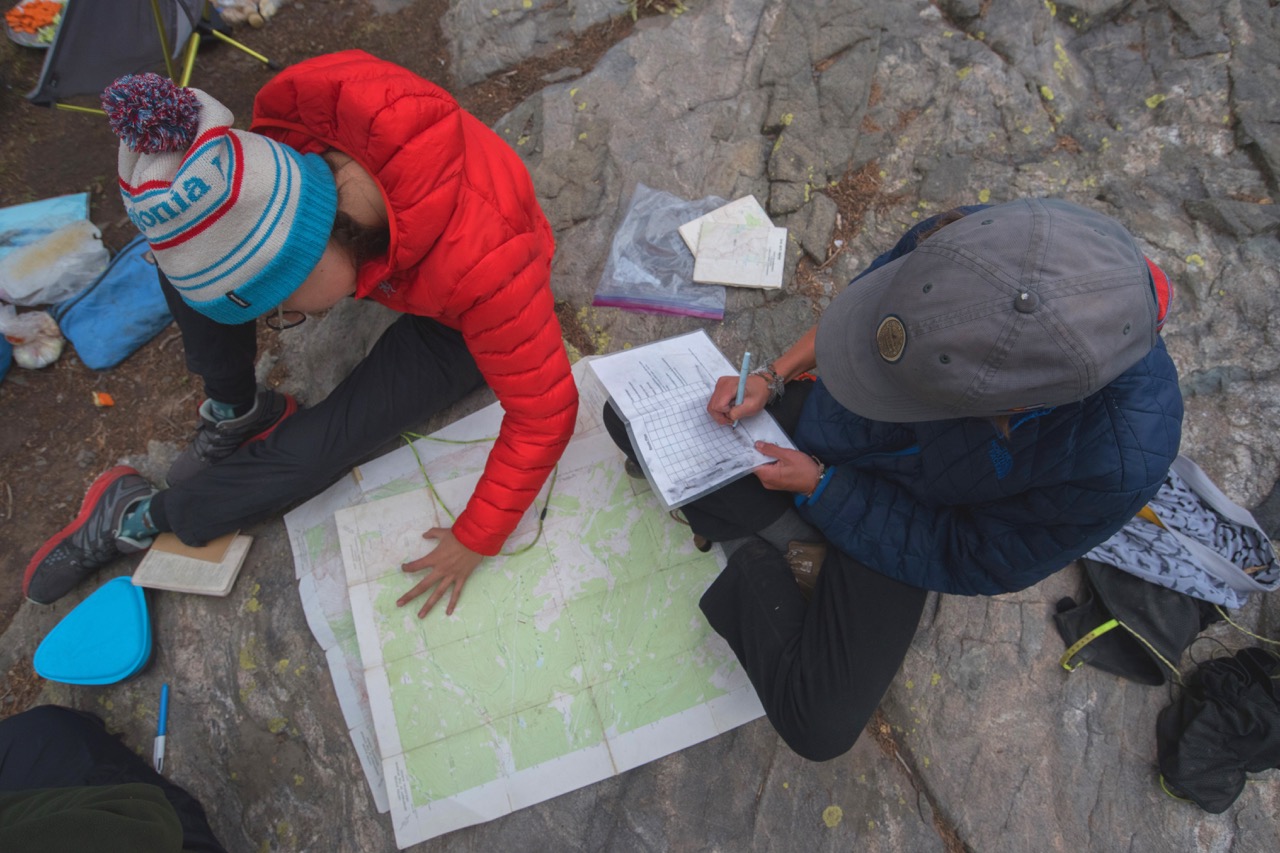

“Wilderness was so bewildering!” he shared. “I didn’t know anything about camping, but the work and the people that I cleared trails with during Wilderness were great and made me feel like I belonged in this special place.”

Encouragement came in the form of Gene Hebert and Gordo Stonington, among others. Gene shared Eric’s comfort with French as their first language, his love for Salsa music and reading in Spanish, and through classes and trips encouraged Eric’s curiosity about the natural world and how to steward it.

“CRMS reinforced and even enhanced my interests in the natural environment and sustainability. Trips to Canyonlands, Escalante, or the daily view of Mt. Sopris.. I wanted to learn more about those places and how to take care of them for others. The work we did during those trips was of service.”

“CRMS reinforced and even enhanced my interests in the natural environment and sustainability. Trips to Canyonlands, Escalante, or the daily view of Mt. Sopris.. I wanted to learn more about those places and how to take care of them for others. The work we did during those trips was of service.”

After graduating from CRMS in 1982, Eric began undergraduate studies in mathematics at Colorado College. After graduation, he worked for five years as a ski instructor in Vail before returning to one of his childhood interests.

“I was admitted to the University of Maryland for a master’s in geography. My original intent wasn’t to get a Ph.D. but to be a working researcher. I received a research assistantship and started working with airborne remote sensing systems on NASA’s C-130 aircraft, making measurements of grasslands in Kansas, conducting experiments in the African Sahel and the Canadian boreal forests, and analyzing the data. Eventually, I really wanted to look at national parks in Venezuela. If you can use satellite information to detect illegal activity like mining within the park boundaries, you can help those parks with their management.”

“Mercury and other pollutants are often used in illegal mining and gold extraction in the Tropics. It leaves a gross yellowish mark where virgin rainforest once stood, and it’s like a moonscape of destruction and contaminants that run off into other river basins,” Satellite imagery can find these telltale signs and alert authorities. “All the data is digital, and we use computers to analyze it, and this enabled me to finally bring together my interests in numbers and natural resource management.”

Eric took a couple of years off to work for the USDA, conducting remote sensing for precision agriculture, which helps farmers use fertilizer only in the places where it’s most needed, rather than an entire field. He also worked on the team developing the next generation of environmental satellites for the US Government, many of which are flying today.

Yet curiosity got the best of him once again, leading to a Ph.D. program in Geography and eventually to NASA as the Coordinator for Earth Science Education and Public Outreach for the Earth Science Division at Goddard, a position focused on building interest in STEM/STEAM education across the D.C./MD/VA/PA regions.

“I wanted my science research to make a difference in somebody’s life. If I could study the Earth and communicate with young students that math and science are fun and can have an impact, that was motivating. I did a lot of work talking with public and private school students and educators about science and STEM careers. It’s one thing to give presentations to my peers, but that doesn’t necessarily make a difference to anyone else. I tried to take a path where the stories and experiences I shared could inspire younger people from diverse backgrounds to get involved in STEM fields.”

Today, Eric and his sons Thomas (age 23) and Lucas (age 20) live in the greater D.C. area, and he also shares time with his wife Brandy in Lancaster, PA. He continues his work for NASA as a Physical Scientist in Goddard’s Biospheric Science Laboratory, where he studies urbanization using fifty years of global satellite images from the Landsat satellite. His team created the Global Manmade Impervious Surface (GMIS) dataset, which can be used to study the impacts of urban development and land use nearly anywhere in the world, from Shanghai to Carbondale.

“Most people don’t know NASA studies cities, but we are really trying to understand the environmental consequences of land use changes—like how water flows off the impervious cover, urban heat islands and heatwaves, air and water quality impacts, etc—or how the planet is changing due to human activity. When you couple cities and climate change, the effects tend to feed on each other. So what’s the future like for the cities of the world, and their inhabitants, with a changing climate?”

His curiosity is also bringing the “hard sciences” to bear on social issues.

“One thing that we’re doing more recently, working with D.C. and Baltimore, is trying to understand how human decisions create the patterns on the land that we measure from space. We would like our data and science to help make the cities of the future more sustainable and to help urban communities become more resilient to the changing climate. There are also quite a few connections to issues such as environmental and social justice. Urban planners and developers in the US, many years ago, drew maps that indicated more investment in certain neighborhoods and not in others—often underinvesting in areas where the poor or minority communities lived. The patterns and issues we see today are a direct result of these human decisions long ago.” And it turns out that those communities most impacted by these decisions tend to also be the ones that may be the least resilient to future climate changes, or who may face additional issues related to rising urban temperatures because of a lack of tree cover and/or open space for example. I like to think of something I call the “Urban Fabric” in the sense of not only the infrastructure that exists in cities, but clearly also the intertwining of the human component in the inhabitants of the cities of the world. “

Over the years Eric has also become a strong proponent of “citizen science,” in which the public—adults and youth—collaborates with scientists and researchers on challenging questions. At the end of July this year, he and his team will launch the GLOBE Observer Land Cover Challenge, which encourages people everywhere to take measurements using a NASA mobile app, called Globe Observer or GO. “We want on-the-ground information, or what we call “ground-truth”, so we can compare to what our satellites measure, and we can only verify that with people participating in doing science with us.” I look forward to making some measurements at the school myself at our 40th class reunion.

While he says that the value of curiosity was planted during his early childhood in Venezuela, CRMS was the catalyst that set him on his path.

“In retrospect, (coming to CRMS) was probably one of the best decisions my parents and I made, even if it meant leaving home at a fairly young age. I was standing at one of those proverbial forks on the road of life that we all know, and I am so grateful I took the road to Carbondale, CO.”

To celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Landsat series of satellites, you and your family can help Eric and NASA with the GLOBE Observer (GO) Land Cover Challenge, which runs from the end of July to the end of August 2022. You get to use the NASA GO mobile phone app to record land cover wherever you are and share it with scientists like Eric. Read More here.

Eric’s work with decades of satellite data enables research into land use and impervious cover change over time–including these images of Carbondale from 1986 and 2022.

MYCRMS

MYCRMS

Virtual Tour

Virtual Tour